The Real Difference Between Sugar and High-Fructose Corn Syrup

Home » Eat Empowered » The Real Difference Between Sugar and High-Fructose Corn Syrup

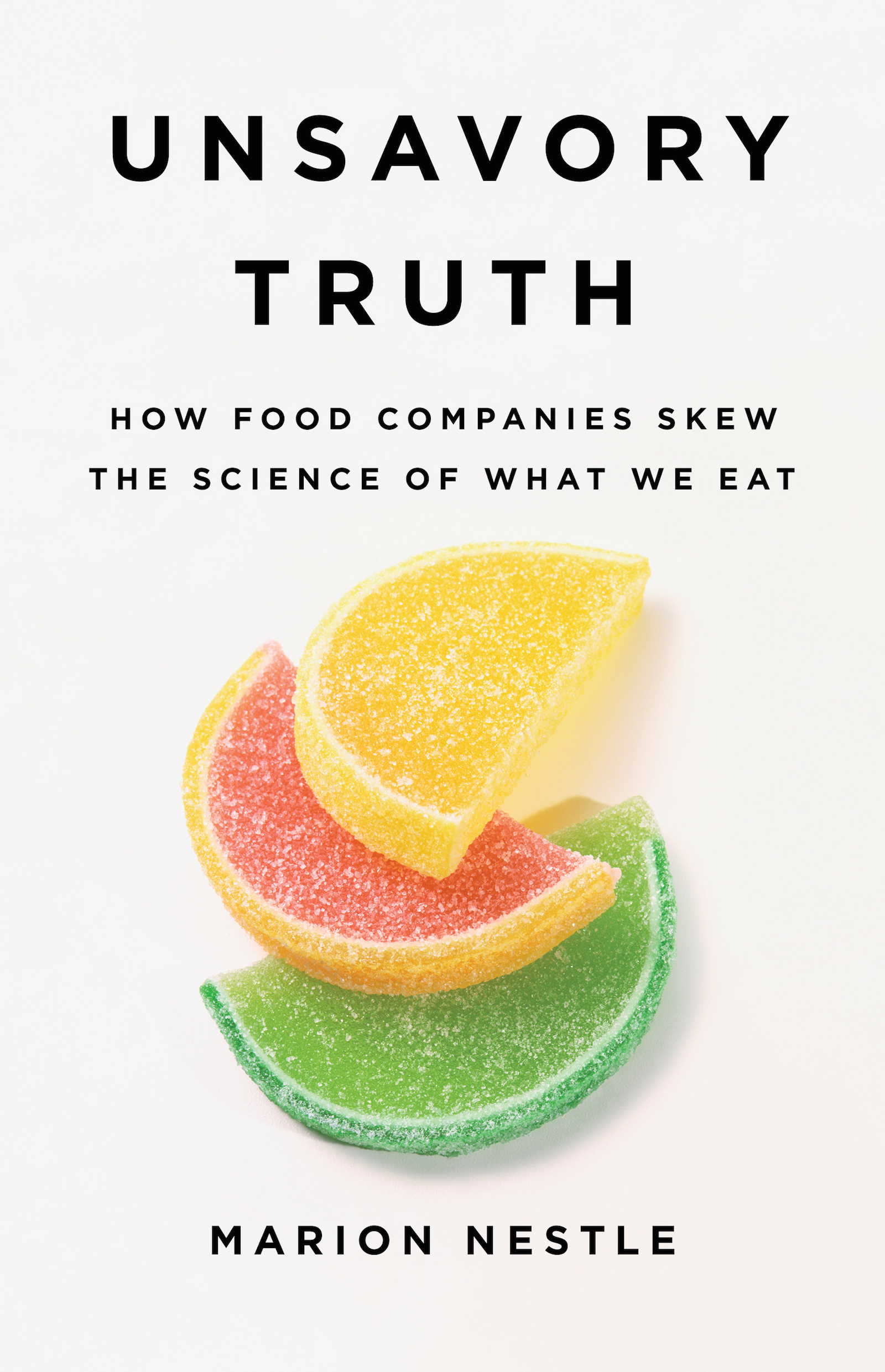

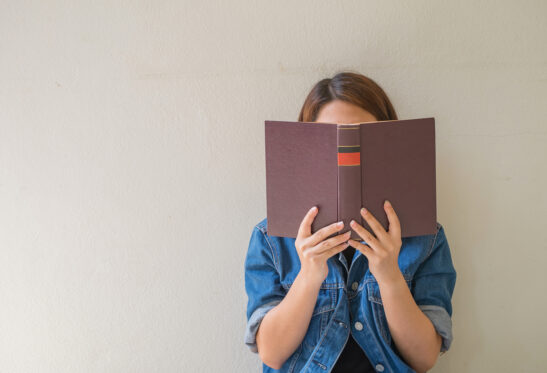

Food and nutrition expert Marion Nestle, PhD, was one of the first people to draw attention to how corporate influence and government policy and politics impact how and what we eat and our perception of what constitutes a healthy diet. Her book Food Politics started it all, and she’s written several additional best-sellers since. Her newest, Unsavory Truth: How Food Companies Skew the Science of What We Eat goes deep into how food companies—both makers of foods you’d consider unhealthy and healthy—influence nutrition research, policy, and public opinion. In this excerpt from the chapter “How Sweet It Is: Sugar and Candy as Health Foods,” she tackles the difference between sugar and high-fructose corn syrup.

If your company produces sugar or products made with it, you have a public relations problem. Sugars are today’s food enemy number one, toxic by some reports. How much is safe? None, claims science journalist Gary Taubes; sugar is responsible for obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, gout, and Alzheimer’s disease. Without going nearly that far, the American Heart Association advises six teaspoons as the upper daily limit for women and children. Men are bigger; they get to have nine. Public health recommendations are slightly more generous. The World Health Organization and the US dietary guidelines both advise limiting sugars to 10 percent of daily calories, which works out to about twelve teaspoons a day on average. All these recommendations refer to added sugars. Nobody is or should be concerned about the sugars naturally present in whole fruits and vegetables; the amounts are low, and the sugars are accompanied by vitamins, minerals, and fiber. In contrast, added sugars provide calories devoid of other nutrients.

RELATED: Is the Natural Sugar Found in Whole Foods Healthier Than Added Sugar?

If you sell sugary products, what to do? Invoke the playbook, of course. Cast doubt on science linking sugars to poor health. Resist regulation, fund front groups, manage the media—and be sure to fund your own research. In 2014, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) summarized the sugar industry’s tactics for undermining policy: attack the science, spread misinformation, deploy industry scientists, and influence academics.

As we now know from the discovery of decades-old documents from a bankrupt sugar company, this industry was engaged in casting doubt on inconvenient science as early as the 1960s. Then, the Sugar Research Foundation, the forerunner of today’s Sugar Association, was spending 10 percent of its research budget on studies to counter research suggesting an association between sugar and the risk of heart disease. To distract dental professionals from suggesting limits on sugar to prevent tooth decay, the foundation lobbied the National Institute of Dental Research to fund studies on anything except sugar: plaque removal, vaccines, fluoride treatments, mouth bacteria, or tooth brushing. This effort succeeded; the 1971 National Caries Program promoted the alternative methods to reduce tooth decay but said nothing about the need to reduce exposure to sugary foods and drinks.

Today’s Sugar Association wants to convince you that “sugar” refers only to crystals refined from beets and cane—sucrose, in biochemical terms. Soon after my book Food Politics came out in 2002, I did a radio interview in which I mentioned that soft drinks contain sugar and water but are otherwise nutritionally useless. I soon received a certified letter from a lawyer for the Sugar Association accusing me of making “numerous false, misleading, disparaging, and defamatory statements about sugar.” What had I said? “As commonly known by experts in the field of nutrition, soft drinks have contained virtually no sugar (sucrose) in more than 20 years. The misuse of the word ‘sugar’ to indicate other caloric sweeteners is not only inaccurate, but it is a grave disservice to the thousands of family farmers who grow sugar cane and sugar beets.”

RELATED: 4 Reasons You Have Sugar Cravings

This lawyer had to be kidding. By “other caloric sweeteners,” the Sugar Association means high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS)—the sweetener that must not be named, apparently. In biochemical terms, sucrose and HFCS are not much different; both contain glucose and fructose sugars. Sucrose is glucose and fructose stuck together (50 percent each), but the two are quickly separated by intestinal enzymes. HFCS is about 45 percent glucose and 55 percent fructose, already separated. Both end up in the body as “free” (meaning separated) glucose and fructose. At that stage, their source is irrelevant.

Until corn started to be grown for ethanol fuels, HFCS was much cheaper than sucrose, so food processors put it in every food or drink they could, beginning in the early 1980s, just as the prevalence of obesity was rising rapidly. The increasing use of HFCS occurred in parallel with increasing obesity—an association, not necessarily a cause. “High-fructose” sounds ominous, given that excess fructose ends up as fat in the liver. HFCS came to be viewed as a cheap and potentially harmful ingredient, best avoided. In reality, both sucrose and HFCS are sugars. Both are best consumed in small amounts.

As I see it, the most critical difference between sucrose and HFCS is their representation by different—and warring—trade associations.

The Sugar Association represents the producers and processors of sucrose from sugar cane and sugar beets; it wants no part of HFCS. The Corn Refiners Association (CRA) represents the industry that processes corn into HFCS; it wants you to think of HFCS as “corn sugar.” As part of this fight for market share, sugar producers sued the CRA to prevent it from applying the word “sugar” to HFCS. The Union of Concerned Scientists’ report I referred to earlier reproduced documents released during this lawsuit. They include an email from the president of the Sugar Association calling for research to prove that sucrose is healthier than HFCS: “Question the existing science. Call for more science that compares sucrose to free fructose and free glucose. The majority of science on this issue compares . . .apples to apples.”

The Corn Refiners Association, in contrast, wants to position HFCS as equivalent to sucrose. I learned this when I inadvertently got caught up in a CRA advertising campaign. In 2010, an executive at Ogilvy Public Relations asked if I would meet with his client, CRA president Audrae Erickson. Shortly after our meeting, my statements about the approximate biochemical equivalence of sucrose and HFCS appeared on the CRA’s website. I asked to have them removed. Erickson’s response? Take us to court.

I was not about to do that, but I later learned more about how the CRA operated from a New York Times account of the legal battles between the two trade associations. Reporter Eric Lipton based his investigation on emails and other documents, which he posted online in categories; one was titled “Using Marion Nestle.” The emails in that section refer to my criticism of a study done by investigators at Princeton University reporting that rats fed HFCS gained more weight than those fed sucrose. Because the study had not provided data on the rats’ calorie intake, I did not think its conclusion was justified, and I said so on my blog. My post solved a problem for the CRA; their emails stated, “Agreed, we cannot look too orchestrated. Nestle piece works best for us on Princeton study” and “We’ve already sent the Nestle piece out to reporters (which I think has been relatively successful).”

Other emails referred to tests of the sugar composition of drinks sweetened with HFCS done by investigators at the University of Southern California (USC). Their tests showed the average fructose content to be higher than 55 percent, with some drinks containing as much as 65 percent.But Rick Berman, head of the Center for Consumer Freedom, assured the CRA, “If the results contradict USC, we can publish them, or maybe even reach out to Marion Nestle & give her the exclusive so she can be a conduit to media. If for any reason the results confirm USC, we can just bury the data.”

The Center for Consumer Freedom? Use me as a conduit? Bury the data?

Excerpted from Unsavory Truth: How Food Companies Skew the Science of What We Eat, with permission from Basic Books.

The Nutritious Life Editors are a team of healthy lifestyle enthusiasts who not only subscribe to — and live! — the 8 Pillars of a Nutritious Life, but also have access to some of the savviest thought leaders in the health and wellness space — including our founder and resident dietitian, Keri Glassman. From the hottest trends in wellness to the latest medical science, we stay on top of it all in order to deliver the info YOU need to live your most nutritious life.

RECENT ARTICLES

Want a sneak peek inside the program?

Get FREE access to some of the core training materials that make up our signature program – Become a Nutrition Coach.

Get Access"*" indicates required fields

Eat Empowered

Eat Empowered